Musings on the Berlin Interpretation

If you’re familiar at all with Roguelike games, you may have heard of the Berlin Interpretation, an attempt at a standard definition to answer the question “What is a Roguelike?”.

This was widely regarded as a bad idea, and made a lot of people very angry (with mangled apologies to Douglas Adams).

As is traditional, and required, for anyone working on anything roguelike, roguelite, or rogue-adjacent, here is a blog post on the subject. (Don’t blame me… I don’t make the rules!)

The original text of the Berlin Interpretation is below. And I have issues with it.

The Berlin interpretation is split into two sections; a preamble, and a list of general principles, further subdivided into “high value” and “low value” principles.

==Preamble==

This definition of "Roguelike" was created at the International

Roguelike Development Conference 2008 and is the product of a

discussion between all who attended. The definition at

http://www.roguetemple.com/roguelike-definition/ was used as the

starting point for the discussions. Most factors are newly phrased,

new factors have been added, some factors have been removed.

==General Principles==

"Roguelike" refers to a genre, not merely "like-Rogue". The genre is

represented by its canon. The canon for Roguelikes is ADOM, Angband,

Crawl, Nethack, and Rogue.

This list can be used to determine how roguelike a game is. Missing

some points does not mean the game is not a roguelike. Likewise,

possessing some points does not mean the game is a roguelike.

The purpose of the definition is for the roguelike community to better

understand what the community is studying. It is not to place

constraints on developers or games.

==High value factors==

====Random environment generation====

The game world is randomly generated in a way that increases

replayability. Appearance and placement of items is random.

Appearance of monsters is fixed, their placement is random.

Fixed content (plots or puzzles or vaults) removes randomness.

====Permadeath====

You are not expected to win the game with your first character. You

start over from the first level when you die. (It is possible to save

games but the savefile is deleted upon loading.) The random

environment makes this enjoyable rather than punishing.

====Turn-based====

Each command corresponds to a single action/movement. The game is not

sensitive to time, you can take your time to choose your action.

====Grid-based====

The world is represented by a uniform grid of tiles. Monsters (and

the player) take up one tile, regardless of size.

====Non-modal====

Movement, battle and other actions take place in the same mode. Every

action should be available at any point of the game. Violations to

this are ADOM's overworld or Angband's and Crawl's shops.

====Complexity====

The game has enough complexity to allow several solutions to common

goals. This is obtained by providing enough item/monster and item/item

interactions and is strongly connected to having just one mode.

====Resource management====

You have to manage your limited resources (e.g. food, healing potions)

and find uses for the resources you receive.

====Hack'n'slash====

Even though there can be much more to the game, killing lots of

monsters is a very important part of a roguelike. The game is player-

vs-world: there are no monster/monster relations (like enmities, or

diplomacy).

====Exploration and discovery====

The game requires careful exploration of the dungeon levels and

discovery of the usage of unidentified items. This has to be done anew

every time the player starts a new game.

==Low value factors==

====Single player character====

The player controls a single character. The game is player-centric,

the world is viewed through that one character and that character's

death is the end of the game.

====Monsters are similar to players====

Rules that apply to the player apply to monsters as well. They have

inventories, equipment, use items, cast spells etc.

====Tactical challenge====

You have to learn about the tactics before you can make any

significant progress. This process repeats itself, i.e. early game

knowledge is not enough to beat the late game. (Due to random

environments and permanent death, roguelikes are challenging to new

players.)

The game's focus is on providing tactical challenges (as opposed to

strategically working on the big picture, or solving puzzles).

====ASCII display====

The traditional display for roguelikes is to represent the tiled world

by ASCII characters.

====Dungeons====

Roguelikes contain dungeons, such as levels composed of rooms and

corridors.

====Numbers====

The numbers used to describe the character (hit points, attributes

etc.) are deliberately shown.Let’s go through this definition point-by-point and see what we think about it. (Or more accurately, what I think about it, but you’re sure to agree with me, right? Right??)

To be fair, the Preamble and General Principle sections do state that games that do not implement all of the features in the list aren’t necessarily not roguelikes, but it seems to me that’s just a case of hedging their bets.

High Value Factors

We’ll start with the “high-value” factors. These are the factors that the authors of the Berlin Interpretation feel are most important for the roguelike genre.

Random Environment Generation

The game world is randomly generated in a way that increases

replayability. Appearance and placement of items is random.

Appearance of monsters is fixed, their placement is random.

Fixed content (plots or puzzles or vaults) removes randomness.Okay, so we’ve already run into a problem. The first sentence is okay, if a little vague. Randomly generating a world does not in any way guarantee replayability. The random process needs to be guided somehow. Admittedly, I’m nit-picking a little here, so let’s assume that the random procedural generation is sufficiently constrained to create consistently playable levels.

The second sentence, regarding the random appearance of placement and items is also problematic. Yes, random placement of items is okay, but what if we want to have a set piece (e.g. a beginning village such as in Caves of Qud 🔗 that isn’t random. Does that mean our game is no longer a roguelike? No, that would be ridiculous, but the Berlin Interpretation thinks otherwise. Again, let’s give it the benefit of the doubt and assume that it doesn’t mean truly random. (I.e. no extremely powerful weapons appearing right in front of the player’s start position) and instead allows for shaped randomness. And if this is the case, then it’s only a small stretch to allow fixed set pieces, so I think we can let this one pass.

What about “Appearance of monsters is fixed, their placement is random”? I’m not quite sure what that actually means, as the first part of that could have multiple interpretations, but again let’s be charitable and assume that it means that either the monsters should adhere to a species archetype and/or shaped randomness should be used to decide when (but not where) they are going to appear, to avoid the player being one-shotted by overly powerful monsters as soon as they start the game. And if this is the case, then that lends even more support to the criticisms of the prior two sentences which, as written, make no such guarantees.

Finally, we have an admonition against fixed content, which I have addressed in the last couple of paragraphs, and I have a measured summarization to respond with: No. Fixed content used judiciously does not make a roguelike any less of a roguelike, with Caves of Qud being the perfect example.

Put simply, some things are hard to generate effectively. For example, using prefabricated set-pieces as part of a random level generation algorithm does not detract from the overall randomness in any significant way, especially if it’s only one aspect of the generation; a room could be fixed design, but the some or all of the contents could be randomized, even if only selected from another set of fixed options. (E.g. an abandoned monster lair vs an inhabited monster lair.)

Permadeath

You are not expected to win the game with your first character. You

start over from the first level when you die. (It is possible to save

games but the savefile is deleted upon loading.) The random

environment makes this enjoyable rather than punishing.Well… That seems a bit draconian, doesn’t it? I mean, I can see the point from a gameplay perspective; but I think “enjoyable rather than punishing” is doing a lot of heavy lifting there. Not all roguelikes - and particularly the more modern roguelikes - necessarily lend themselves as well to short repeated runs. This is fine for some players - particularly the more hardcore ones, but is not particularly casual friendly. It’s not very inviting for new and inexperienced players. Personally, I like hardcore as an option, but I typically wouldn’t choose to play that option myself - except in a game specifically designed around short runs (a “coffee break” roguelike). I like the approach that Caves of Qud has taken. In Caves of Qud, there are three game modes available. In the first, the world is much friendlier, and the player can resurrect if they die. In the second, the world is at its normal “friendliness” level, and the player can resurrect upon dying at the most recently visited village, and the third is the standard “hardcore” mode - once you die, that’s it. Of these modes, I prefer the second option.

For the game I’m working on, I’ll probably do something very similar. I also have some ideas regarding different game modes based on how long the player wants to play for, but we are a long way from that point yet.

Back to the point, though… Permadeath is a core feature of roguelikes, but having other options doesn’t make the game any less of a roguelike.

Turn-Based

Each command corresponds to a single action/movement. The game is not

sensitive to time, you can take your time to choose your action.No arguments here. I think that being turn-based is one of the core defining factors of roguelike games. Reflexes not required. That’s not to say that it needs to be purely turn-based to achieve the same effect. For example, there have been plenty of games that implement real-time action that automatically switches to a form a turn-based when something notable happens (such as entering combat). I’d argue that a roguelike using that kind of action mechanism would still be just as much a roguelike, even though it wouldn’t follow this particular principle to the letter. Additionally, just because a game is turn-based, doesn’t mean it has to be obviously so. One of the prototypes I implemented a few years back played as if in real-time as long as the player’s character was moving. As soon as the player stopped, so did time. And behind the scenes, all of the action was implemented using a turn system. Would this have been classified as turn-based by the purists? Honestly, I don’t know. When playing, it was difficult to tell unless you knew what to look for.

Grid-Based

The world is represented by a uniform grid of tiles. Monsters (and

the player) take up one tile, regardless of size.Okay, so this one is just silly. Yes, having the game as tile-based is often the most sensible approach for ease of access and situational understanding for the player, but a requirement? I don’t see why. In my case, I will be implementing a tile-based game, but still, I don’t see why a game that didn’t implement it would not be considered so. For example, imagine a game that borrowed the measure-and-move mechanism from a tabletop skirmish game such as Mordheim 🔗, Necromunda 🔗 or Frostgrave 🔗, but in every other respect was a roguelike. It would still be a roguelike, tile-based or not. (Now, it might also be a tricky game to play, depending on how well the measure-and-move feature was implemented, but that’s another issue.) On top of that, I don’t see the reasoning behind restricting everything to be one tile in size. That just seems like an arbitrary and unnecessary restriction, and one that - thankfully - I think has been ignored. An example that immediately comes to mind is Lost Flame 🔗.

Non-Modal

Movement, battle and other actions take place in the same mode. Every

action should be available at any point of the game. Violations to

this are ADOM's overworld or Angband's and Crawl's shops.I mean, yeah, this one makes sense, but I don’t see it as a necessity. It’s good for immersion, sure, but to have this as a high value factor to be classified as a roguelike. Honestly, I don’t even have much to say about this one. It’s silly. It shouldn’t even be in the list, especially given that two exceptions are listed in the next sentence.

If the bulk of the gameplay is recognizably roguelike, then why would we actually care if there are certain aspects that are modal. If we take this rule to the extreme, then any roguelike that has separate inventory management (or any other type of in-game management screens - e.g. skills, magic, or whatever), or that pops up a modal dialog to display the contents of a book or sign would not be adhering to this rule.

Games like ADOM 🔗 and Caves of Qud use modal interfaces to manage complex systems, such as inventory and character abilities, without detracting from the core gameplay. These modes streamline user experience, demonstrating that modal interfaces can enhance rather than hinder roguelike design. As I said… Silly.

Complexity

The game has enough complexity to allow several solutions to common

goals. This is obtained by providing enough item/monster and item/item

interactions and is strongly connected to having just one mode.I like this guideline, although I think it’s fairly self-evident. It should apply to most games, not just to roguelikes, so I’m not sure it needs to be delineated as a “major roguelike feature” given that it’s actually more of an “interesting game feature” that goes far beyond the roguelike genre. However, it’s still a fairly amorphous goal. How many is “several”? Two? Three? Twenty? And look there, at the end - a total non-sequitur about how this is “strongly connected to having one mode”. Nonsense.

Resource Management

You have to manage your limited resources (e.g. food, healing potions)

and find uses for the resources you receive.Again, as with the previous guideline, I don’t think that this needs to be spelled out. However, it’s also very easy to make this kind of mechanism (colloquially called Hunger Clocks) more onerous than it needs to be. Sure, getting hungry/thirsty/etc. certainly should be part of a traditional roguelike game, but it shouldn’t get in the way of fun. If I spend more time feeding, watering and otherwise tending to my character than actually playing the interesting part of the game, then I’m really not going to have fun. I’m sure some people may enjoy that type of gameplay, but I am not one of them.

One of the most frequent complaints that I’ve noticed about various roguelike games are hunger clocks that get in the way of actually playing and enjoying the game. As a game designer, I would prefer that players enjoy the game rather than be forced to micromanage their character’s bodily needs in lieu.

Hack’n’Slash

Even though there can be much more to the game, killing lots of

monsters is a very important part of a roguelike. The game is player-

vs-world: there are no monster/monster relations (like enmities, or

diplomacy).This principle is overly restrictive, and - in my opinion - only serves to stifle innovation. For example, what’s wrong with being able to improve your characters reputation with a certain faction (e.g. orcs) such that they won’t attack you on sight? To my mind this kind of interactivity only serves to improve the game, and certainly doesn’t make it any less of a roguelike - unless you’re only interested in playing the kind of games that could have been written on forty year old hardware.

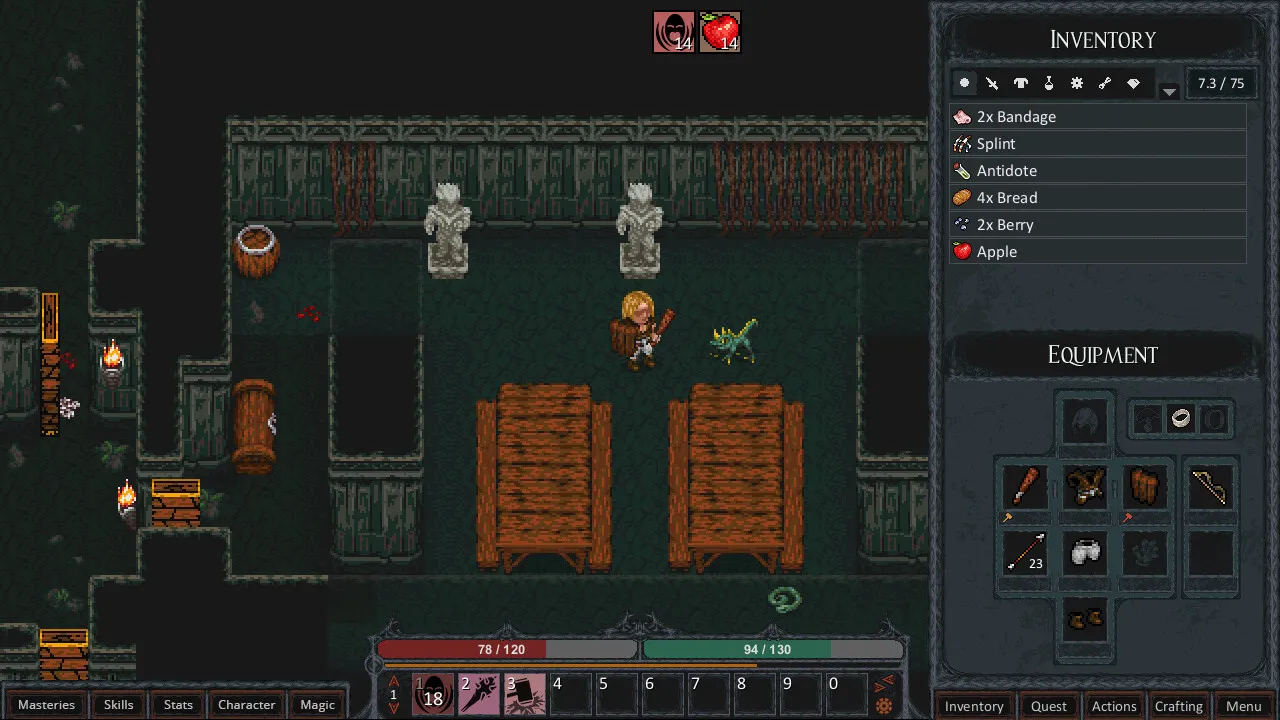

Fortunately, it seems that most modern roguelikes have chosen to ignore this principle, and in my opinion that’s a good thing, with Doors of Trithius 🔗 being the first example that springs to mind.

Exploration and Discovery

The game requires careful exploration of the dungeon levels and

discovery of the usage of unidentified items. This has to be done anew

every time the player starts a new game.Ignoring the fact that this principle assumes that the roguelike will take place in a multilevel dungeon (as has historically been the case, and fortunately ignored by modern roguelikes), this particular principle at least has its heart in the right place. The bit about “unidentified items” is oddly specific. I mean sure - if they have a use in your game then knock yourself out, but I don’t see why it should be a core requirement, or why it necessarily has to be done anew each time a new game is started. There’s nothing wrong with a little bit of meta-progess.

However the general concept of exploration of the unknown is a fundamental part of roguelike gameplay and is in fact necessitated by the random environment generation.

Low Value Factors

You know, I’m not even sure that I agree with how the principles are split into high and low value. There are some in the high value section that I’d push into the low value section (or even completely exclude), and vice versa. I’ll leave it as an exercise for the reader (Hi Joe!) to figure out which is which.

Single Player Character

The player controls a single character. The game is player-centric,

the world is viewed through that one character and that character's

death is the end of the game.Most roguelikes tend to be single player character, but some have party-based gameplay. However most TTRPGs (of which I’d argue that Roguelikes are an attempt to computerize) are, in fact, party-based. The “Single Player Character Only” principle may be too restrictive for modern roguelikes, which benefit from the added complexity, narrative depth, and replayability that multiple characters can offer. Embracing a broader approach can enrich the genre and appeal to contemporary gaming audiences.

Monsters are Similar to Players

Rules that apply to the player apply to monsters as well. They have

inventories, equipment, use items, cast spells etc.It’s fairer if monsters adhere to the same rule system as the player, and this principle has clear advantages in creating a balanced and immersive game world, but it also can pose challenges in terms of variety and balancing. However, of all of the principles so far, this is the one I have the least problem with - and it definitely encourages the development of a sound AI engine to control the monsters’ behavior to sufficiently challenge an advanced player.

Tactical challenge

You have to learn about the tactics before you can make any

significant progress. This process repeats itself, i.e. early game

knowledge is not enough to beat the late game. (Due to random

environments and permanent death, roguelikes are challenging to new

players.)This principle allows the game to offer significant benefits in terms of engagement, replayability, and game design complexity. However, it also presents challenges related to casual appeal, development resources, and time investment that would need to be carefully balanced. However, it also seems a bit redundant - I mean, I’d be hard pressed to think of many video games that don’t offer some form of tactical challenge.

ASCII display

The traditional display for roguelikes is to represent the tiled world

by ASCII characters.So?

Dungeons

Roguelikes contain dungeons, such as levels composed of rooms and

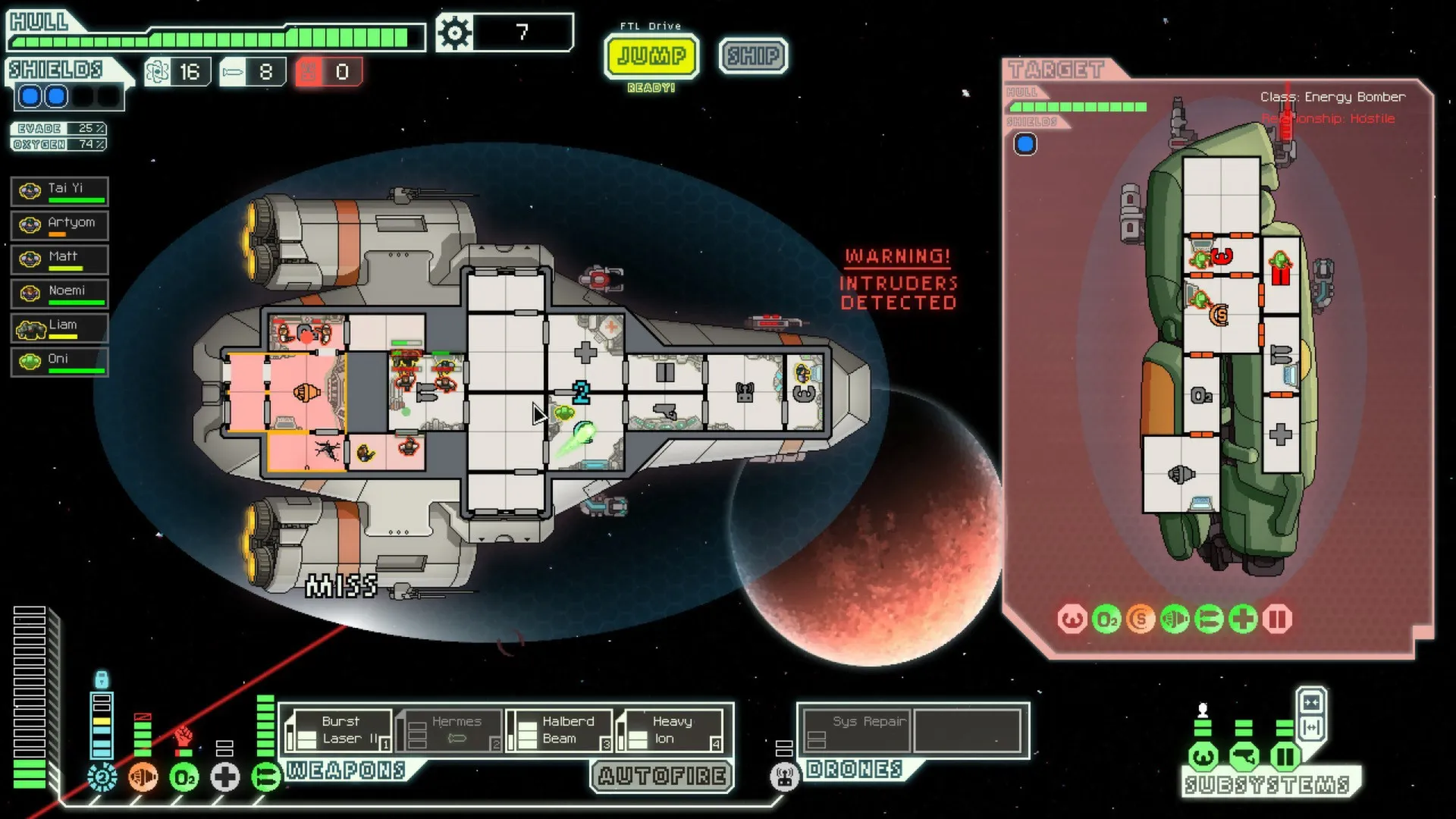

corridors.Sure, in the abstract, but it’s a bit limiting if the intent is to restrict the game to dungeons only. However, as written, this does not imply that restriction. I’m sure a roguelike could be made without dungeons (conceptual or otherwise), and I’d argue that FTL 🔗 would be one contender for that position, but I certainly don’t see a problem with this principle, other than the fact that it’s probably totally unnecessary to even have it. Roguelikes can have dungeons (in one form or other) or not.

Numbers

The numbers used to describe the character (hit points, attributes

etc.) are deliberately shown.To be fair, allowing the player to see the numbers behind the gameplay events enhances transparency, depth, and customization in roguelike games, which in turn allows for strategic planning and detailed character development. However, it can also introduce complexity, potential for min-maxing, and immersion issues.

So, if you want numbers in there, sure, but it’s not necessary as long as the player can clearly evaluate their state at any time. If there’s a better way to do it than numbers, then use that. (For reference, I’ll probably be using numbers unless I can think of something better.)

Final Words

Now, I’ve probably been a bit unfair here, because I’m not sure anyone really takes the Berlin Interpretation seriously anymore. However, I do keep seeing it come up in various forums. Honestly, who cares though, right? If your game “feels” like a roguelike, then it’s a roguelike. But what does that mean? It’s a bit wishy-washy, but it should be clear that if you play the original Rogue (or one of its contemporaries) and then you play another game that purports to be a roguelike, then if it evokes the same gameplay feel, it’s probably a roguelike even if it doesn’t religiously adhere to the Berlin Interpretation. More importantly though, is it fun?

The principles outlined in the Berlin Interpretation serve as a guideline rather than a strict rulebook. While they aim to capture the essence of what makes a roguelike, they can be overly restrictive and fail to account for the genre’s evolution. Modern roguelikes have pushed the boundaries, incorporating innovative mechanics and diverse settings that deviate from these traditional principles.

For instance, the emphasis on “Single Player Character Only” and “Hack’n’Slash” can limit the scope of what roguelikes can achieve. Allowing for party-based gameplay or diplomatic interactions with monsters can enrich the experience and introduce new layers of strategy and narrative depth. Similarly, the insistence on a “Grid-Based” or “ASCII Display” is more of a nostalgic nod than a necessity, as evidenced by visually rich roguelikes like (arguably) Darkest Dungeon 🔗, Slay the Spire 🔗 and FTL.

The principle of “Permadeath” is integral to the roguelike experience, but offering multiple modes can make the genre more accessible without diluting its core challenge. And while “Random Environment Generation” and “Exploration and Discovery” are central to creating replayability and a sense of adventure, incorporating fixed elements judiciously can enhance the overall experience without detracting from the randomness.

Ultimately, the Berlin Interpretation should be viewed as a starting point rather than an endpoint. It provides a framework, but the true measure of a roguelike is in how it engages and challenges players. Whether through innovative mechanics, compelling narratives, or intricate designs, the goal should always be to create a fun and memorable experience.