Building a Zèrtz AI, Part 1: MCTS, Rust, and Hexagonal Symmetry

TLDR

This post is about a work-in-progress MCTS engine for Zèrtz with a Rust backend, Python orchestration, and Panda3D renderer. The code is available at: github.com/hiive/Zertz3D .;

Background

The GIPF project ![]() is a series of abstract strategy games designed by Kris Burm. Each game in the series explores a single mechanical concept (e.g. stacking, captures, mobility, etc.). This elegance makes them interesting targets for AI research (and also a lot of fun to play if you’re a fan of abstract boardgames, as I am – even if I lose most of the time.)

is a series of abstract strategy games designed by Kris Burm. Each game in the series explores a single mechanical concept (e.g. stacking, captures, mobility, etc.). This elegance makes them interesting targets for AI research (and also a lot of fun to play if you’re a fan of abstract boardgames, as I am – even if I lose most of the time.)

Zèrtz ![]() is the first game in the series that I purchased back in 2004 and, as my favorite, is the one I chose to tackle first.

is the first game in the series that I purchased back in 2004 and, as my favorite, is the one I chose to tackle first.

Here’s a brief summary of the rules so that (hopefully) the rest of this article will make sense.

Zèrtz Rules Summary

- Players share a common pool of marbles (6 white, 8 grey, 10 black) on a 37-ring hexagonal board

- On the player’s turn, they must do exactly one of:

- Place and remove: Put any marble from the pool onto an empty ring, then remove an unoccupied edge ring

- Capture: Jump a marble over an adjacent marble into the empty ring beyond it (like checkers). Captures are mandatory. If a capture is available, the player must take it. If the jump creates another capture, they must continue.

- If removing a ring isolates a fully-occupied group from the main board, the player captures those marbles

- The player wins immediately by capturing: 4 white, 5 grey, 6 black, or 3 of each color

And if you really want to read the full rules, I’ve included them behind the content warning box.

Game Mechanics

The overall plan is to build a solid MCTS (Monte Carlo Tree Search) baseline, then integrate neural network guidance in a subsequent phase. This post covers the first phase: game engine implementation, MCTS with various enhancements, migration to Rust, and hyperparameter tuning. The mechanics present several challenges for search algorithms.

Mandatory Captures

If a player can jump an opponent’s marble, they must do so. If that jump creates another capture opportunity, they must take that as well. A single “move” can cascade into a forced sequence of jumps. From a search perspective, this creates narrow channels in the game tree where there is no decision to be made – the player is simply following the rules until the forced sequence terminates (although there may still be situations where the player has to choose which marble to capture when more than one capture move is available from the current position).

Dynamic Board Topology

After placing a marble, the player removes an edge ring from the board. By mid-game, the 37-ring starting configuration might be reduced to 25 rings. Positions that were adjacent become separated. Clusters of rings can become isolated from the main board and are removed entirely, along with any marbles on them. The adjacency graph changes on every turn.

Hexagonal Symmetry with Board-Size Dependence

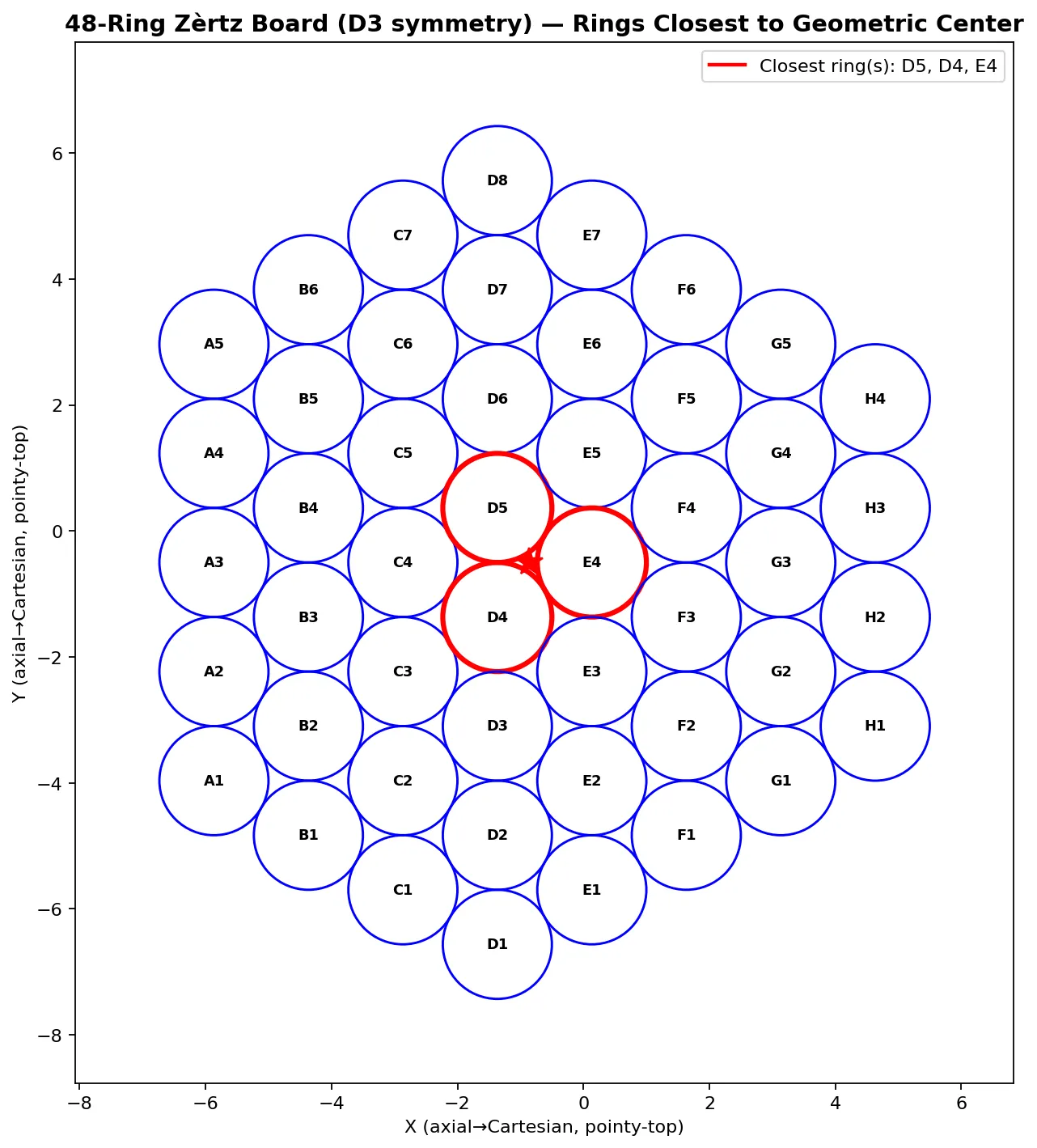

The standard 37-ring board has D6 symmetry; six rotations combined with mirroring yields twelve equivalent orientations, as does the 61-ring board. The 48-ring board, however, has only D3 symmetry (halving the number of equivalent orientations). The 48-ring board lacks the full hexagonal symmetry that the 37 and 61-ring boards possess, which has implications for state canonicalization, discussed below.

Notation

Zèrtz uses a standard notation system for recording games. The board positions are labeled with coordinates (letters for columns, numbers for rows). The official notation system is documented here ![]() . The conventions below follow that reference.

. The conventions below follow that reference.

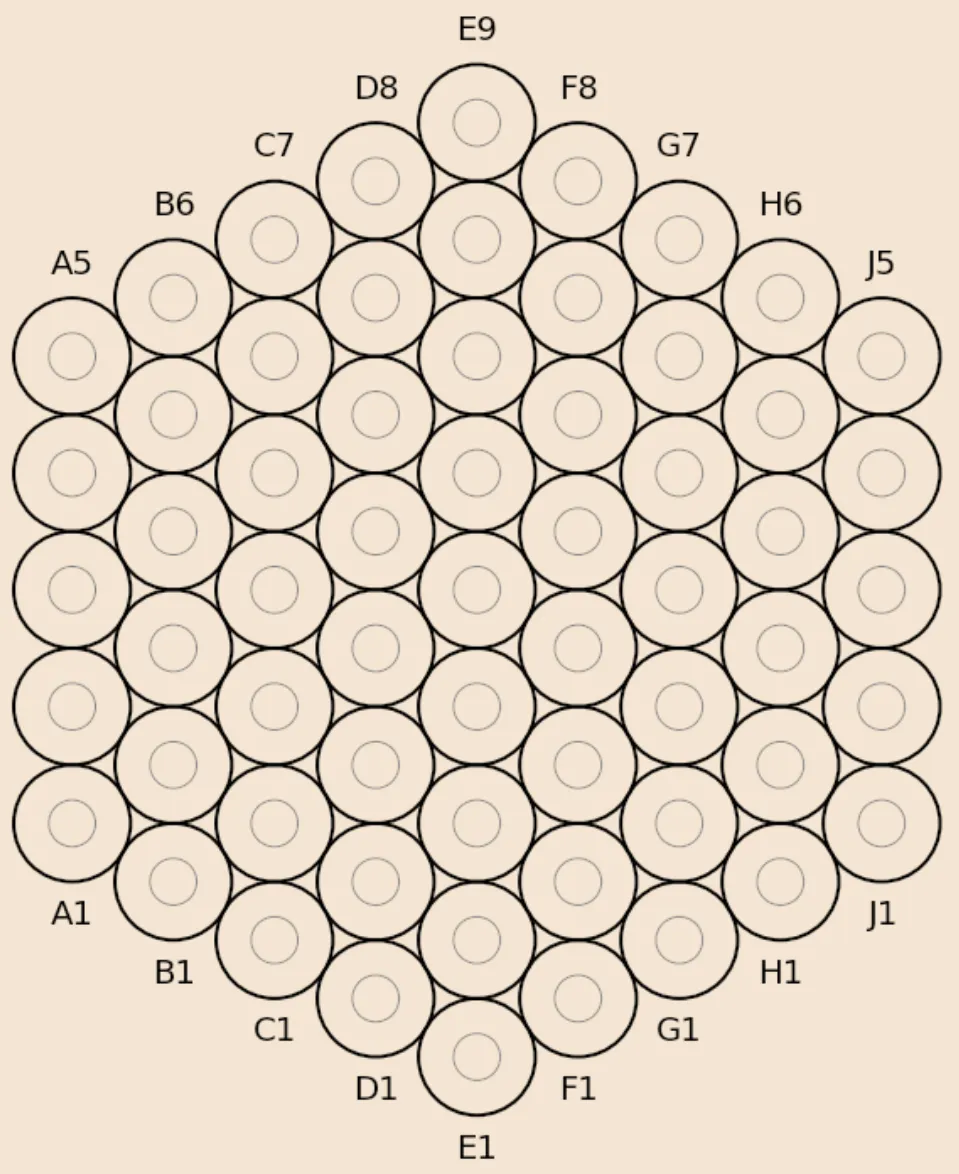

Board notation (e.g., d4, f2): The human-readable notation used in game records. Column letters (a-g for 37-ring, a-h for 48-ring, a-j for 61-ring, skipping i) combined with row numbers, as can be seen in the following image showing the 61-ring board.

Note that the implementation provides conversion functions between notation and grid coordinates.

Marble colors: W = White, G = Grey, B = Black

Placement moves follow the format [Color][Destination],[Removed Ring]:

Wd4,b2— place a(W)hitemarble ond4, remove the ring atb2Bf6,d1— place a(B)lackmarble onf6, remove the ring atd1

Capture moves are prefixed with x, showing the jumping marble’s path:

x e3Wg3– marble ate3jumps tog3, capturing the(W)hitemarble atf3(the midpoint)x d1Gd3Wd5– marble atd1jumps tod3(capturing(G)reyatd2), then continues tod5(capturing(W)hiteatd4)

Isolation captures append the claimed marbles after a placement:

Bd7,b2 x Wa1Wa2– place(B)lackond7, removeb2, capture isolated(W)hitemarbles ona1anda2

Pass is recorded as - (occurs when a player has no legal move).

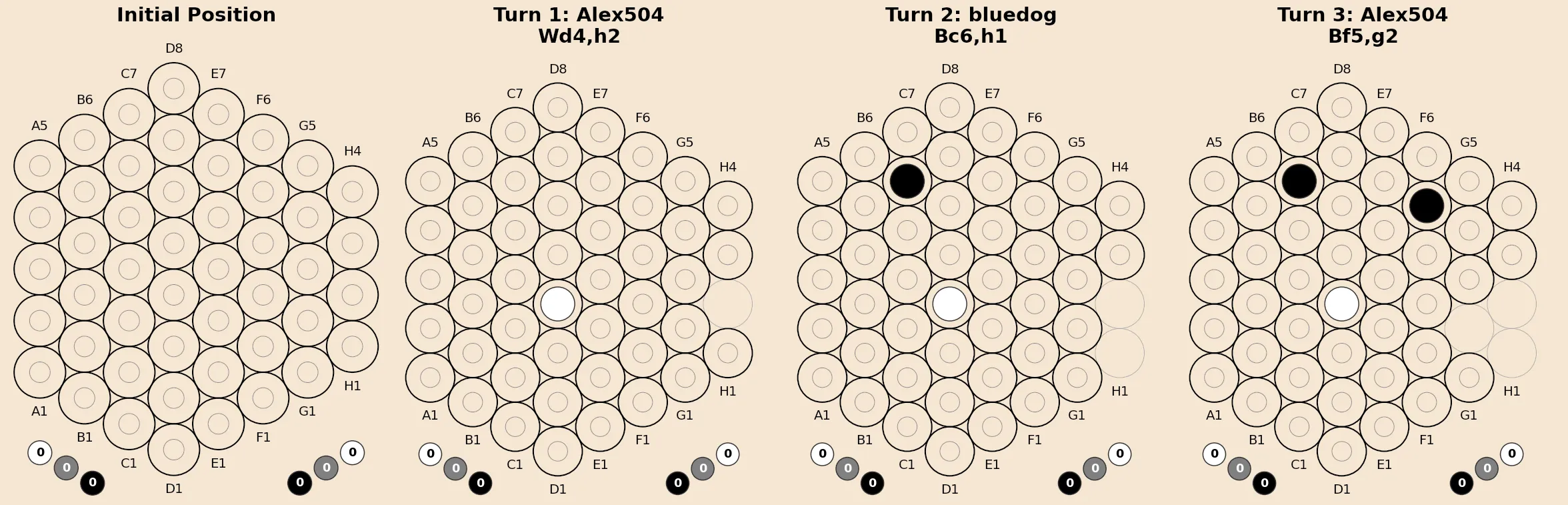

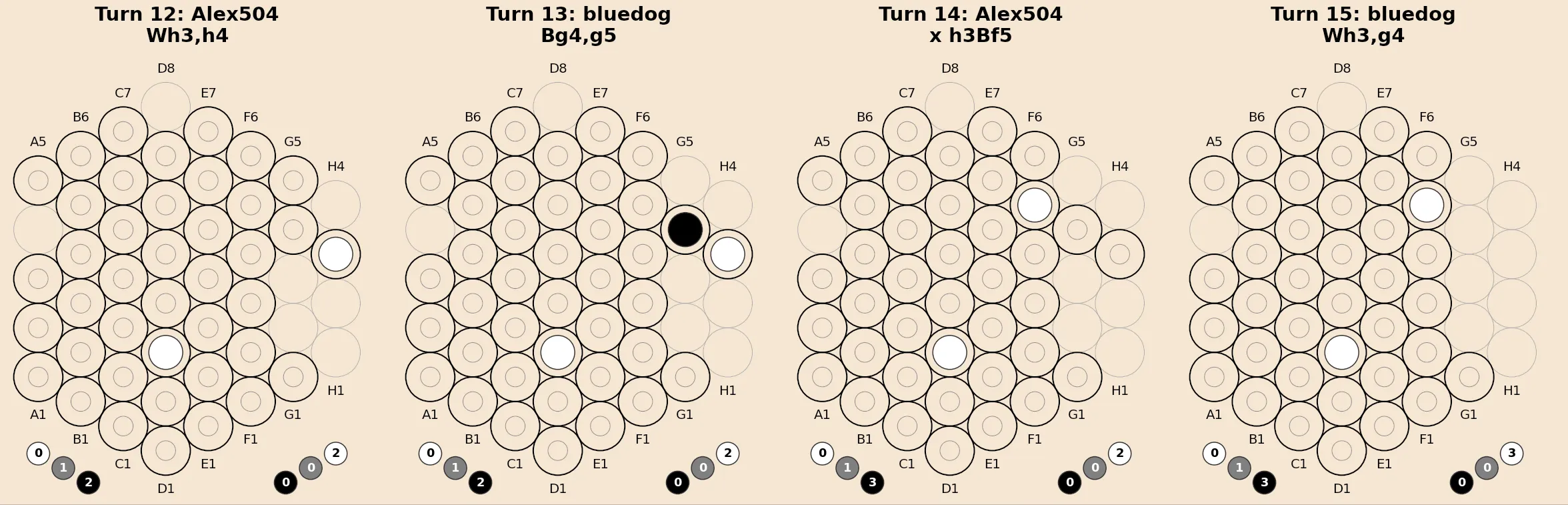

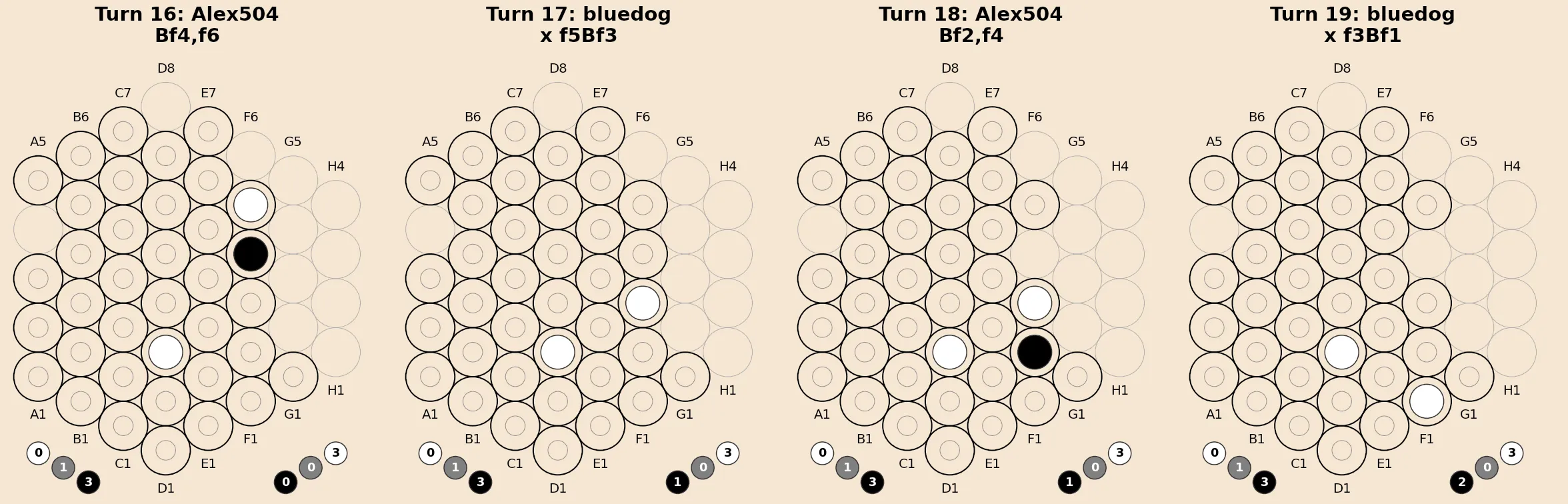

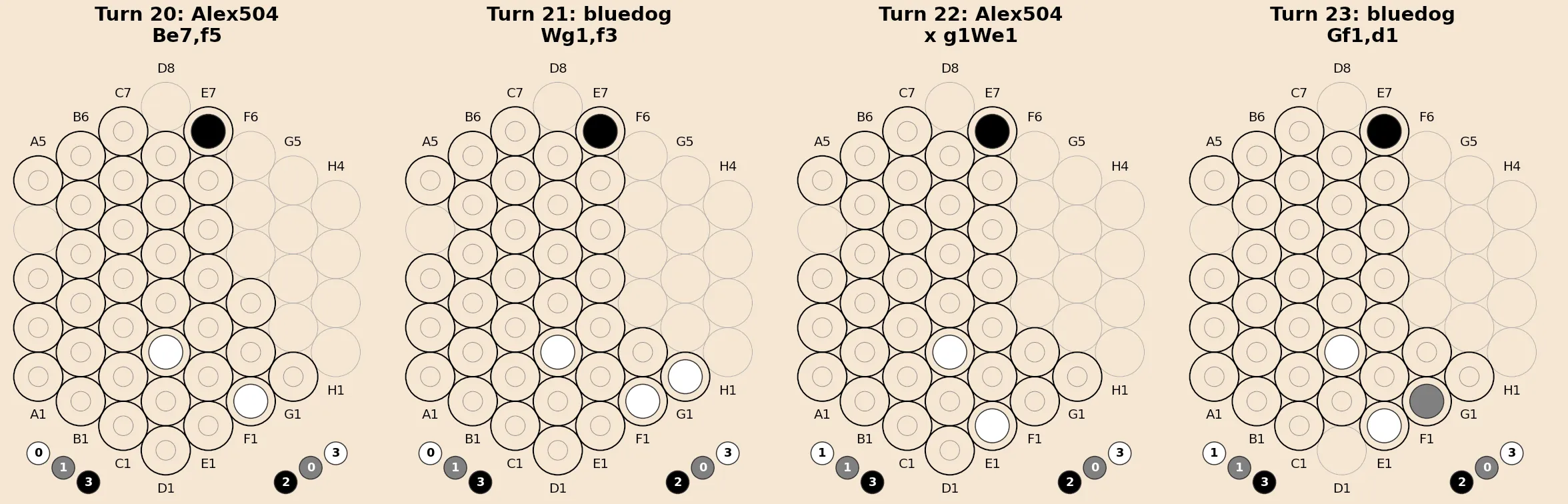

Move Sequence Example

Wd4,d1

Ge5,c3

Bf6,d2

x c2We4

-(W)hiteond4, removed1(G)reyone5, removec3(B)lackonf6, removed2- Capture from

c2toe4, capturing the(W)hitemarble ond3 - Pass

The game sequence visualization shown here, between Alex504 and Bluedog on boardspace.net ![]() , uses this notation to label each turn.

, uses this notation to label each turn.

Game Engine

Before implementing any AI, I needed to make sure the game engine was complete and fully working. Developing this took longer than expected, and required substantial refactoring once I decided that it would be nice to support additional games in future[1].

Rules Implementation

Zèrtz has rules that appear simple but contain subtleties that only emerged during implementation.

Isolated region detection

When rings are removed, portions of the board can become disconnected from the main cluster. These orphaned regions (and any marbles occupying them) remain in the game until fully occupied by marbles, whereupon the marbles within are captured by the player who placed the marble that filled the region.

Capture chain enumeration

A capture can create new capture opportunities that must be taken. This means a single player action might involve multiple jumps (potentially with choice points), and from the AI’s perspective, this entire sequence constitutes one atomic move rather than one move per mandatory jump.

Termination conditions

The game can end via standard win (collecting sufficient marbles of specific colors), board exhaustion, marble pool depletion, consecutive passes, or position repetition. Each condition requires different detection logic, and I discovered several games during testing that either terminated incorrectly or failed to terminate when they should have.

Engine Validation

I validated the engine by replaying games from Boardspace.net ![]() and comparing the results. When my implementation disagreed with theirs, I examined the rules to determine which was correct (which was usually them, except in a couple of cases with older game files). This process uncovered several edge cases in my implementation.

and comparing the results. When my implementation disagreed with theirs, I examined the rules to determine which was correct (which was usually them, except in a couple of cases with older game files). This process uncovered several edge cases in my implementation.

Architecture

The current (more-or-less final) architecture uses Python for orchestration and Rust for performance-critical components. The split occurred during development (discussed in the migration section below), but this is the current structure:

from hiivelabs_mcts import zertz

mcts = zertz.ZertzMCTS(

rings=37,

exploration_constant=1.41,

widening_constant=12.0,

fpu_reduction=0.5,

use_transposition_table=True

)

action = mcts.search(spatial_state, global_state, iterations=5000)The Rust code is exposed via PyO3 ![]() . Python handles file I/O, rendering, and player management. Rust handles game logic and MCTS.

. Python handles file I/O, rendering, and player management. Rust handles game logic and MCTS.

Visualization

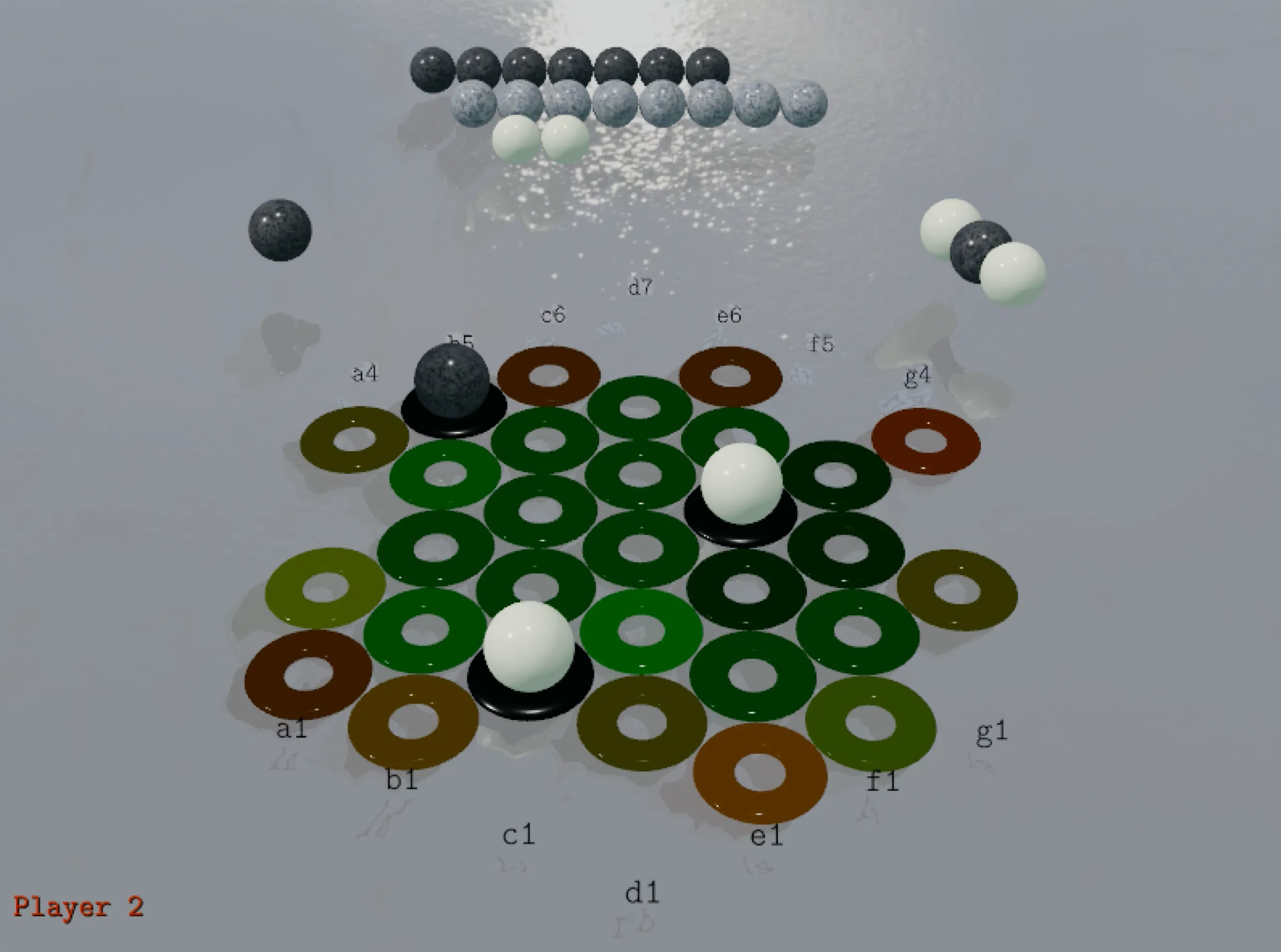

Building the Panda3D renderer early proved valuable (and kept my motivation going). Observing the AI play reveals bugs that my unit tests missed – incorrect ring state tracking, unrecognized capture chains, and similar issues become immediately apparent visually.

The highlight mode is particularly useful for debugging AI behavior. It displays which moves the search is considering, with coloring based on visit count or estimated value.

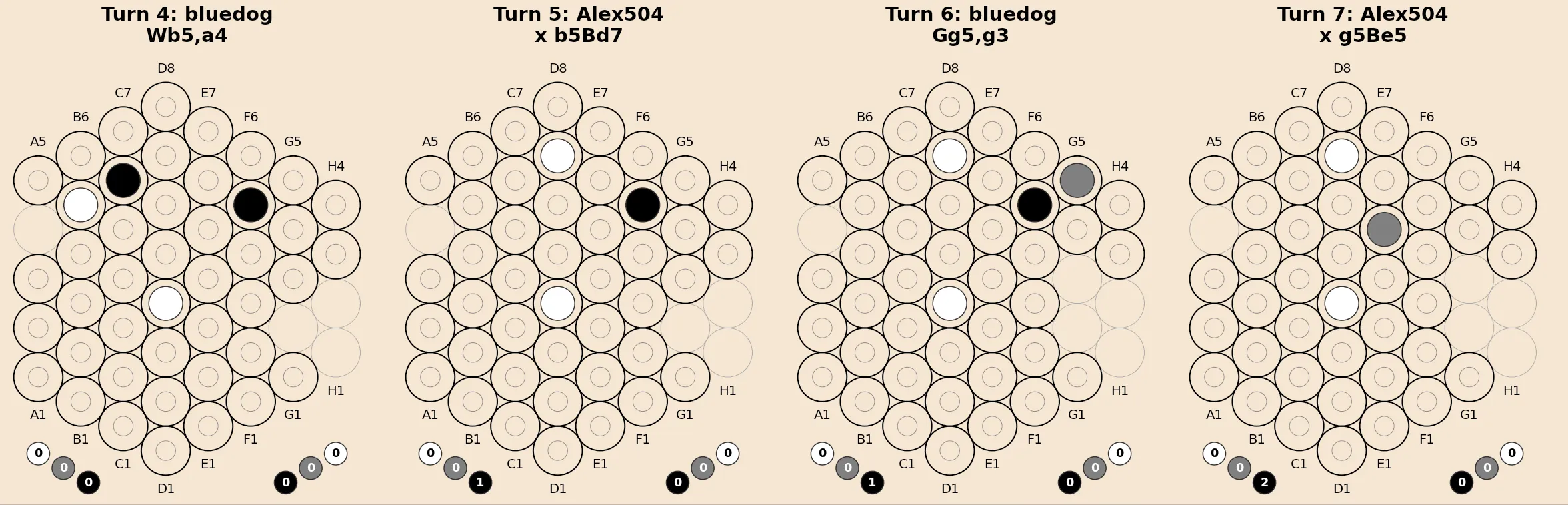

The following image shows a snapshot of the MCTS “thinking” about which move to play. It’s considering a placement move. Possible placement locations are shown in green, with the stronger green colors being more favored placements. At the same time it’s considering which ring to remove. Those are shown in red with the stronger reds indicating the more favored removal candidates. Some of those rings are shown in brown/yellow, indicating that the MCTS is considering them as both placement AND removal candidates (although obviously if it chooses a ring as a placement candidate it then gets excluded from removal).

Clicking on the above image will display a video of the full game between the MCTS player (Player 2) and the Random Player (player 1). You will see that the random player considers all possible moves equally (indicated by the unvarying color highlights).

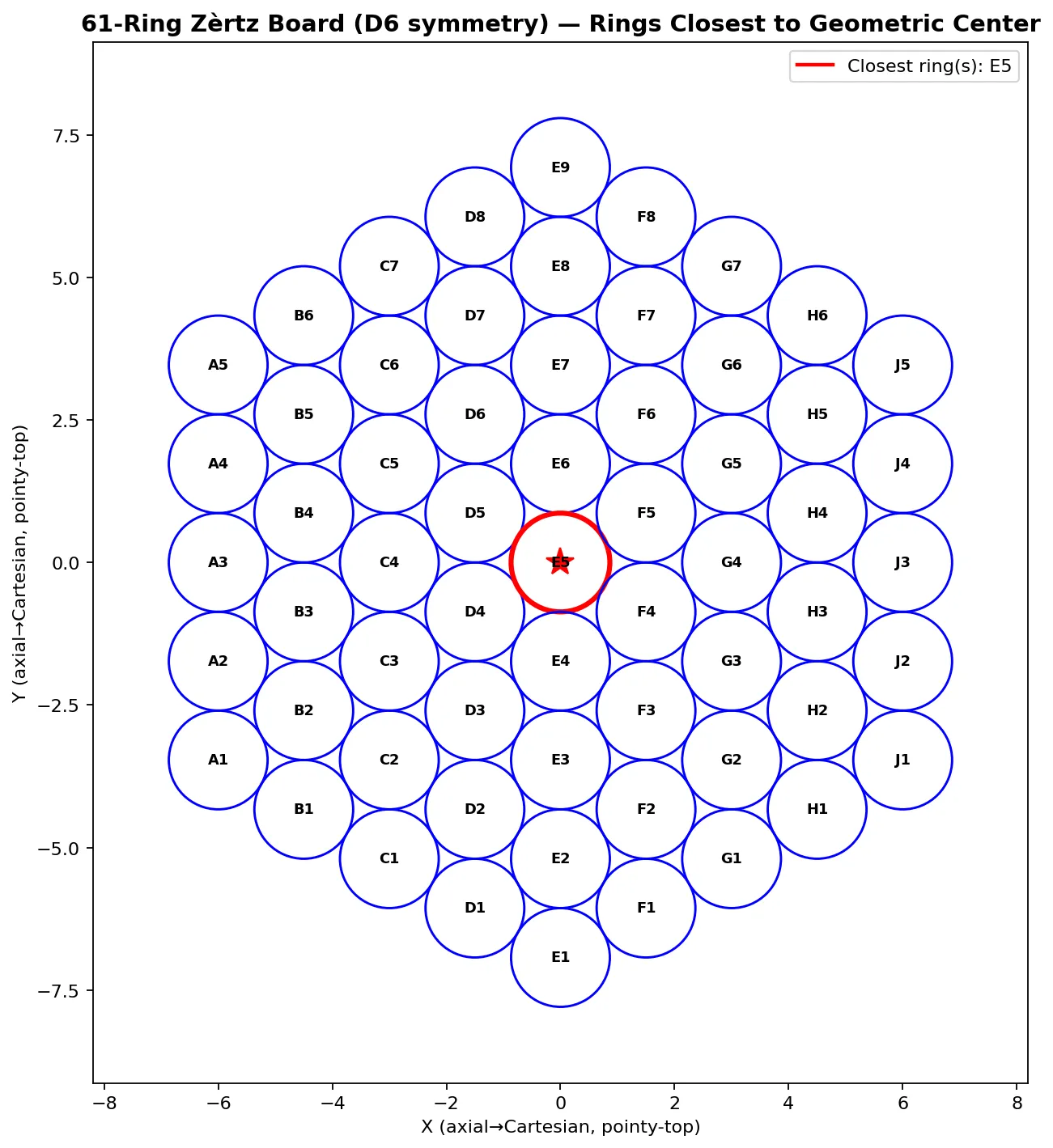

Alongside the 3D renderer, a separate diagram toolkit generates static board images for documentation and analysis. This Matplotlib-based system can render single positions, turn-by-turn game sequences (like the game visualization shown earlier), and canonicalization comparisons showing equivalent board orientations. The toolkit reads standard notation files, Boardspace SGF replays, or transcript logs, and outputs PNG or SVG at configurable resolutions. For the canonicalization analysis shown later in this post, the toolkit renders all symmetry-equivalent orientations side-by-side, making it easy to verify that the canonical form selection is correct.

Internal Representation

Representing a hexagonally connected space isn’t immediately straightforward; the hexagonal Zèrtz board is represented internally as a rectangular array with a validity mask. This section describes the coordinate system, state tensor structure, and the mapping between logical board positions and array indices.

Hexagonal-to-Rectangular Mapping

A hexagonal board does not map naturally to a rectangular grid. The implementation embeds the hexagonal layout within a square array, with invalid positions masked out.

| Number of Rings | Grid Dimensions | Valid Positions |

|---|---|---|

| 37 | 7×7 | 37/49 |

| 48 | 8×8 | 48/64 |

| 61 | 9×9 | 61/81 |

The layout mask is a 2D boolean array indicating which grid positions correspond to valid board rings. For a 37-ring board on a 7×7 grid:

y\x 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

0 A4 B5 C6 D7 .. .. .. (4 valid)

1 A3 B4 C5 D6 E6 .. .. (5 valid)

2 A2 B3 C4 D5 E5 F5 .. (6 valid)

3 A1 B2 C3 D4 E4 F4 G4 (7 valid)

4 .. B1 C2 D3 E3 F3 G3 (6 valid)

5 .. .. C1 D2 E2 F2 G2 (5 valid)

6 .. .. .. D1 E1 F1 G1 (4 valid)

--------

37 totalPositions marked .. are outside the hexagonal board and are never accessed during game logic.

- The array origin

(y=0, x=0)corresponds to coordinateA4. - Moving right (

+x) increments the column letter; moving down (+y) steps toward smaller-numbered ranks. - Positions marked

..are outside the playable hex and remain zero across all layers. - This layout is consistent across Python and Rust.

For the 48- and 61-ring boards the same convention applies with widths 8 and 9, respectively, yielding larger trapezoidal hex layouts.

The generate_standard_layout_mask function constructs this mask programmatically based on the ring count.

Coordinate Systems

The implementation uses axial coordinates for rotation and reflection operations. Given grid coordinates

Axial coordinates are centered on the board centroid. In this system, hexagonal rotations and reflections have simple arithmetic forms.

Rotation by 60°:

Reflection across the q-axis:

For 48-ring boards, only the D3-valid rotations (0°, 120°, 240°) are generated. The 60° rotation is not a valid symmetry for the 48-ring layout because the even-width grid (8×8) lacks the six-fold rotational symmetry present in odd-width grids.

Spatial State Tensor

The board state is represented as a 3D tensor of shape (layers, height, width). Each layer is a binary mask (values 0.0 or 1.0) encoding one aspect of the position:

| Layer | Contents |

|---|---|

| 0 | Ring presence (1 = ring exists at this position) |

| 1 | White marble presence |

| 2 | Grey marble presence |

| 3 | Black marble presence |

| 4×t | Capture flag (chain continuation marker) |

The capture layer (at index 4×t) is necessary for enforcing Zèrtz’s mandatory chain capture rule. When a capture is made and further captures are available from the landing position, this layer is set to 1.0 at that position, indicating that the marble must continue capturing. The layer is cleared when no more captures can be made.

Note that unlike the ring and marble layers, the capture flag is not stored per timestep – there is only one capture layer at the end of the tensor. This is because the flag is transient: it only matters during the current turn. By the next timestep, either the chain completed or it didn’t, and the marble positions tell the story. This design may be revisited depending on neural network training results.

For pure MCTS with random rollouts, history depth t=1 is sufficient – a 37-ring board uses shape (5, 7, 7) with the capture flag at layer 4. For neural network training, configurable history depth stores previous board states. With t=5, the tensor shape becomes (21, 7, 7): layers 0-3 hold the current position, layers 4-7 hold the previous position, layers 8-11 the position before that, and so on, with the single capture flag at layer 20.

Only positions where layer 0 is 1.0 are active board positions. Marble layers have 1.0 where a marble of that color occupies the ring, 0.0 otherwise.

This representation has several advantages:

- Sparse efficiency: As rings are removed, layer 0 becomes increasingly sparse. Operations that iterate over valid positions can check layer 0 first.

- Neural network compatibility: The tensor format is directly consumable by convolutional or graph neural network (GNN) architectures. Each layer functions as a feature channel.

- Canonicalization simplicity: Transforming the board state under rotation, reflection, or translation operates uniformly across all layers – the same coordinate mapping applies to rings and marbles.

Global State

Information that does not have spatial structure is stored separately in a 10-element vector:

| Index | Contents |

|---|---|

| 0–2 | Marble supply counts (white, grey, black) |

| 3–5 | Player 1 captured counts (white, grey, black) |

| 6–8 | Player 2 captured counts (white, grey, black) |

| 9 | Current player (0 or 1) |

Initial supply values are 6 white, 8 grey, and 10 black (except in Blitz games which use 5, 7, 9). Move history for repetition detection is tracked separately at the game level, not in the state tensor. This may be revisited at some point for inclusion in the state tensor.

The MCTS operates primarily on the spatial state for position evaluation, with global state consulted for move generation (e.g., which marble colors can be placed) and terminal detection (e.g., whether a player has achieved a winning collection).

Layer Configuration

The number of spatial layers can be extended for richer state representations. The BoardConfig structure specifies layers_per_timestep, which defaults to 4 (ring + 3 marble colors), and a history depth parameter t that controls how many previous board states to include. The total layer count is (4×t)+1, where the extra layer is the capture flag. Additional feature layers could encode:

- Legal move masks

- Derived features (e.g., distance from edge, connectivity)

For pure MCTS with random rollouts, t=1 (5 layers) is sufficient. Neural network training would need to use higher values of t to capture temporal patterns in board positions.

Canonicalization

Canonicalization converts symmetry-equivalent board states into a single, consistent representation. In Zèrtz, the hexagonal board has rotational and reflective symmetry, meaning the same logical game state can appear in multiple physical orientations. Additionally, when edge rings are removed during gameplay, the remaining board cluster can be translated (shifted) within the grid while maintaining validity.

Why Canonicalization Matters

Without canonicalization, the search algorithm treats rotationally or reflectionally equivalent positions as distinct states, unnecessarily re-analyzing positions it has already evaluated.

For MCTS with transposition tables, canonicalization provides:

- State space reduction: Multiple equivalent states map to one canonical form, reducing the effective state space

- Efficient lookup: Two equivalent positions always produce the same hash key

- Consistent evaluation: The same position always receives the same cached value, regardless of how it was reached

For neural network training, canonicalization will provide:

- Data efficiency: The network learns from one orientation and generalizes to all equivalent positions

- Consistent targets: Equivalent positions map to identical training examples

Symmetry Groups

The applicable symmetry group depends on board size:

37-ring and 61-ring boards have D6 (dihedral) symmetry:

- 6 rotations: 0°, 60°, 120°, 180°, 240°, 300°

- 6 reflections: mirror combined with each rotation

- Total: 12 equivalent orientations

48-ring boards have only D3 symmetry:

- 3 rotations: 0°, 120°, 240°

- 3 reflections

- Total: 6 equivalent orientations

The reduced symmetry of the 48-ring board arises from the 8×8 hex grid geometry. The hexagonal layout on an even-width grid lacks the full hexagonal symmetry present in odd-width grids (7×7 for 37 rings, 9×9 for 61 rings).

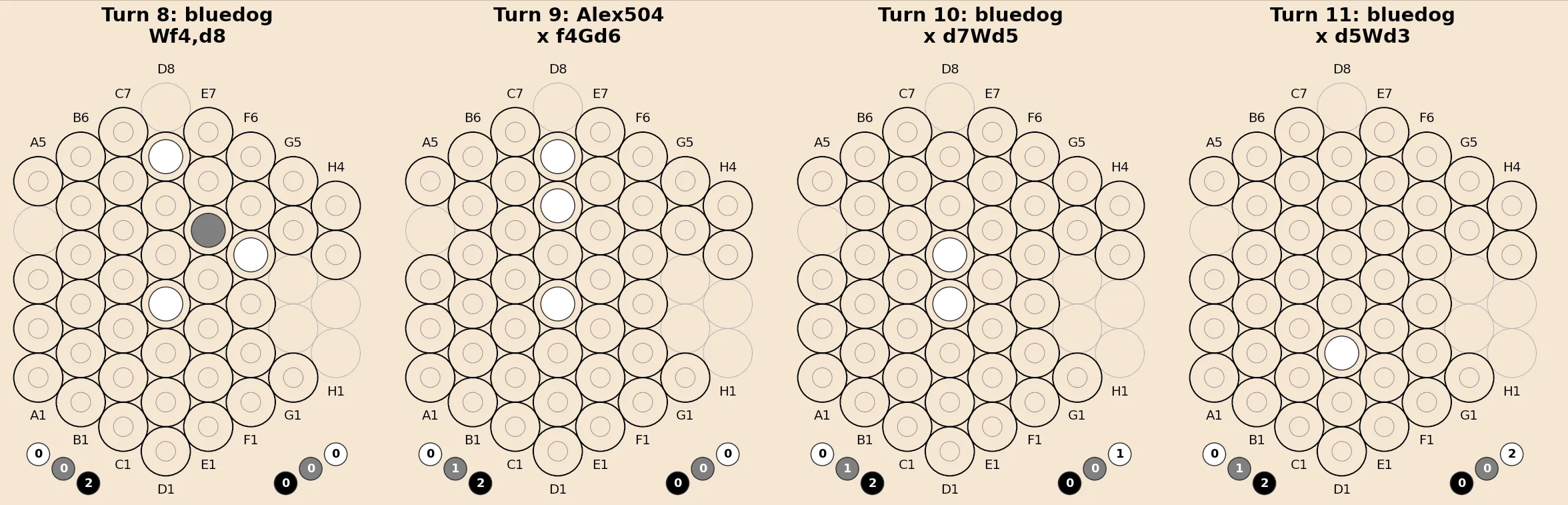

The following images explain the inherent symmetry of each board configuration, as well as the ring(s) closest to the geometric center (centroid), the origin of any rotation operations.

Translation Equivalence

Translation becomes relevant as the board shrinks. When edge rings are removed, the remaining cluster of rings may no longer be centered in the coordinate grid. Two positions that differ only in their placement within the grid should be recognized as equivalent.

Consider a late-game position where only 15 rings remain, forming a connected cluster. This cluster could occupy multiple locations within the 7×7 coordinate grid, depending on which edge rings were removed earlier in the game. Without translation canonicalization, each placement would be treated as a distinct state.

Bounding box calculation: The algorithm first computes the minimal rectangle containing all remaining rings – the positions where

Not all offsets within the bounding box range produce valid states. The hexagonal layout is not rectangular – positions near the corners of the grid are invalid. A translation that moves a ring into an invalid grid position is rejected.

Impact on state space: Translation canonicalization becomes increasingly valuable as the game progresses. In the opening, with all 37 rings present, only one translation is valid (the identity). By mid-game, with 25 rings remaining, there may be 5–10 valid translations. Combined with 12 rotational/reflective symmetries for D6 boards, this yields 60–120 equivalent representations of each position.

Transform Notation

Transforms are encoded as strings with the following components:

Rotations:

R0– identity (no transformation)R60,R120,R180,R240,R300– rotation by the specified angle

Reflections:

MR{angle}– mirror first, then rotate (e.g.,MR60,MR120)R{angle}M– rotate first, then mirror (e.g.,R60M,R120M)

Translations:

T{dy},{dx}– translate by (dy, dx) in grid coordinates

Combined transforms use underscore notation:

T{dy},{dx}_{rotation}– translation followed by rotation/reflection- Example:

T-2,1_R120means translate by (-2, 1), then rotate 120°

When translation is combined with rotation/mirror, translation is applied first:

This ordering is important for consistency and for computing inverse transforms.

Note that the

The Canonicalization Algorithm

The algorithm finds the lexicographically minimal representation across all equivalent states:

- Generate candidate translations: Compute the bounding box of remaining rings. For each valid offset that keeps all rings within the board layout, add a candidate translation.

- Generate candidate symmetries: Based on board size, enumerate all rotations and reflections in the applicable symmetry group (D6 or D3).

- Evaluate all combinations: For each (translation, symmetry) pair:

- Apply translation to the board state

- Apply the rotation/reflection

- Compute a lexicographic key over valid board positions

- Select minimum: The transform producing the smallest key becomes the canonical form.

- Compute inverse: Calculate the inverse transform for mapping actions back to the original orientation.

The lexicographic key is computed over the board layers only (ring presence and marble positions), masked to valid grid positions:

def _canonical_key(self, state):

masked = (state[self.BOARD_LAYERS] * self.board_layout).astype(np.uint8)

return masked.tobytes()Lexicographic ordering is a total ordering. For any two different byte strings, one is always definitively less than the other. This guarantees:

- Uniqueness: There is always exactly one minimum across all symmetry-equivalent forms

- Determinism: No matter which orientation you start with, you always arrive at the same canonical state

- Independence: The canonical form depends only on the logical position, not on how it was reached

Inverse Transforms

To map actions or positions back from canonical form to the original orientation, the inverse transform is required.

Rotation inverses:

| Forward | Inverse |

|---|---|

R60 | R300 |

R120 | R240 |

R180 | R180 |

In general,

Reflection inverses:

| Forward | Inverse |

|---|---|

MR(k) | R(-k)M |

R(k)M | MR(-k) |

Mirror-then-rotate inverts to rotate-then-mirror, and vice versa.

Translation inverses:

Combined transform inverses: Both the operations and their order are reversed. If the forward transform is

Examples:

T1,0_R60→ inverse isR300_T-1,0T2,1_MR120→ inverse isR240M_T-2,-1

Action Transformation

When the board state is canonicalized, actions must also be transformed to remain valid. An action in the original coordinate system must be mapped to canonical coordinates before search, and the selected action must be mapped back via the inverse transform before execution.

For placement moves, this involves transforming both the destination ring coordinate and the ring-to-remove coordinate. For capture moves, the entire jump sequence — start position, intermediate positions, and landing positions — must be transformed.

The implementation provides transform_action and inverse_transform_action methods that handle both placement and capture move formats.

Transform Control

The canonicalize_state method accepts a TransformFlags parameter to control which symmetries are applied:

from game.zertz_board import TransformFlags

# All transforms (rotation + mirror + translation)

canonical, transform, inverse = board.canonicalize_state(

transforms=TransformFlags.ALL

)

# Only rotation and mirror (no translation)

canonical, transform, inverse = board.canonicalize_state(

transforms=TransformFlags.ROTATION_MIRROR

)

# No transforms (identity only)

canonical, transform, inverse = board.canonicalize_state(

transforms=TransformFlags.NONE

)Disabling translation is useful for analysis or when the computational overhead of translation enumeration is undesirable. Disabling all transforms returns the state unchanged with identity transform R0.

Results

Transposition table hit rates during MCTS range from 60–80%. This represents a substantial fraction of the search tree that does not require re-exploration.

The measured overhead is approximately 0.5–1ms per canonicalization call. For D6 boards with translation, this involves evaluating up to

Limitations

Arbitrary canonical form: The lexicographic comparison imposes an arbitrary ordering with no strategic meaning. Any consistent total ordering would work equally well. The current choice simply guarantees that equivalent positions map to identical keys.

Incomplete symmetry exploitation: The implementation does not detect partial symmetries that may exist in specific board configurations. A board state with additional reflective symmetry beyond D6/D3 is not recognized as such. Exploiting these cases would require computing the symmetry group of each configuration, adding complexity for marginal benefit.

Translation search cost: When many rings have been removed, the number of valid translations grows. The algorithm tests each candidate by applying the translation and verifying validity, which scales with

Hash collisions: The transposition table uses Zobrist hashing on canonical state keys. Zobrist hashing assigns a random 63-bit number to each possible feature (ring at position, marble at position, supply count, captured count, current player). The hash of a state is the XOR of all feature values that are “active” in that state. XOR operations are fast, and the technique supports incremental updates (though the current implementation recomputes the full hash). The 63-bit values provide an extremely low collision rate (~1 in 2^63).

Despite the low collision probability, collisions can still occur. When they do, using incorrect cached values would corrupt the search. The implementation handles this by storing the full canonical state alongside each transposition entry and using chaining: if two different states hash to the same value, both are stored in a linked list. On lookup, the chain is searched for an exact state match. In practice, chains rarely exceed one or two entries.

Rust Migration

Motivation

I initially implemented multi-threaded MCTS with virtual loss in Python, but Python’s Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) meant that threading performed sub-optimally; additional threads did not translate to proportionally increased throughput. I looked at various Python-based workarounds (including the free-threaded version of Python 3.14) but ultimately decided to convert the MCTS and game logic implementations to Python-callable Rust code.

Three main factors motivated this decision:

GIL-free parallelism: Python’s GIL prevents true multi-threaded execution. The parallel MCTS implementation spawned threads, but they could not run simultaneously. Rust does not have this limitation (though as discussed below, this turned out to matter less than expected).

Allocation patterns: MCTS creates and discards tree nodes at high frequency. Python’s garbage collector handles this automatically, but GC pauses during search introduce latency. Rust’s ownership model eliminates garbage collection entirely and allows more deliberate control over memory layout.

PyO3 integration: The Rust-Python boundary via PyO3 is clean enough that the Python orchestration layer could remain unchanged. Only the performance-critical path needed to be replaced.

Process

The migration followed a disciplined process:

- Write parity tests comparing Python and Rust outputs on identical inputs

- Port one component at a time (game logic first, then MCTS)

- Verify identical results before removing Python code

The parity test file grew to over 400 lines of code. This level of testing caught bugs in hash collision handling and move ordering that would have been difficult to diagnose otherwise.

Results

The Rust backend is substantially faster. I do not have clean before/after benchmarks because I removed the Python MCTS code before being rigorous about measurement, which is a mistake I will not repeat[2]. The subjective difference during development was significant: tuning runs that would have been impractical became feasible.

Parallel MCTS: A Surprising Result

One of my primary motivations for the Rust migration was GIL-free parallelism. With true multi-threading available, I implemented parallel MCTS with thread-local RNG and virtual loss. The results were unexpected: parallel search was slower than serial.

Configuration Throughput

---------------------------------------------

Serial + widening + RAVE 7562 iter/s

Serial baseline 5042 iter/s

Parallel 4 threads 4472 iter/s

Parallel 8 threads 4485 iter/s

Parallel 16 threads 4513 iter/sAdding threads made performance worse, not better. The culprit is lock contention at tree nodes. All threads start at the root and must acquire a mutex on node.children to select the best child. With shallow trees (typical for 1000–5000 iterations), threads spend most of their time waiting for locks rather than doing useful work.

Virtual loss helps threads diverge eventually, but early iterations are serialized. With shallow trees, there’s insufficient depth for threads to spread out. Additionally, progressive widening, which improves serial performance by focusing search, exacerbates the problem by reducing the branching factor and concentrating threads on fewer paths.

Parallel MCTS works well when:

- Trees are deep (50,000+ iterations): threads have room to diverge

- Simulations are slow: simulation time dominates lock overhead

- Branching is high: more paths for threads to explore independently

Zèrtz has none of these properties at typical iteration counts. The combination of progressive widening (reducing effective branching), fast simulations (game terminates quickly), and moderate iteration budgets means threads compete rather than cooperate.

The lesson: serial MCTS with advanced features (progressive widening, FPU) outperforms naive parallelization by 70%. Parallel search remains available for tournament settings with very high iteration counts, but is disabled by default.

Generic Architecture

During development, I refactored the Rust codebase to support multiple games through a trait-based architecture. The MCTSGame trait defines the interface any game must implement:

pub trait MCTSGame: Send + Sync + 'static {

type Action: Clone + Eq + Hash + Send + Sync;

fn get_valid_actions(&self, spatial: &ArrayView3<f32>, global: &ArrayView1<f32>) -> Vec<Self::Action>;

fn apply_action(&self, spatial: &mut ArrayViewMut3<f32>, global: &mut ArrayViewMut1<f32>, action: &Self::Action);

fn is_terminal(&self, spatial: &ArrayView3<f32>, global: &ArrayView1<f32>) -> bool;

fn get_outcome(&self, spatial: &ArrayView3<f32>, global: &ArrayView1<f32>) -> i8;

fn canonicalize_state(&self, spatial: &ArrayView3<f32>, global: &ArrayView1<f32>) -> (Array3<f32>, Array1<f32>);

fn hash_state(&self, spatial: &ArrayView3<f32>, global: &ArrayView1<f32>) -> u64;

// ... additional methods

}This design enables zero-cost abstraction through Rust’s monomorphization. The generic MCTS code specializes to each game at compile time with no runtime overhead.

To validate the architecture and provide a minimal reference implementation, I implemented Tic-Tac-Toe alongside Zèrtz. While trivial as a game, Tic-Tac-Toe exercises the full trait interface: state representation, move generation, terminal detection, and canonicalization (D4 dihedral symmetry for the 3×3 board). The complete implementation is under 500 lines including comprehensive tests.

Having a second game implementation proved valuable beyond architecture validation. Bugs in the generic MCTS code that happened to work for Zèrtz were exposed when running against Tic-Tac-Toe’s different state shape and symmetry group. The simple game also serves as documentation — anyone extending the engine to support new games can follow the Tic-Tac-Toe implementation as a template.

Hyperparameter Tuning

With the Rust backend operational, I could run experiments that would have been impractical before.

Setup

The tuning harness (scripts/analysis/search_hyperparameters.py) supports grid search and random search, logs results with timestamps and git commit hashes for reproducibility, and generates visualization scripts.

A typical tuning run would look like this:

uv run python scripts/analysis/search_hyperparameters.py \

--method grid \

--games 100 \

--iterations 1500 \

--config data/tuning/example_config.yamlAnd the reference config.yaml would look something like this:

# MCTS Hyperparameter Tuning Configuration for quick test

# =======================================================

mode: grid

game:

rings: 37

iterations: 250 # quick test

games_per_config: 100

seed: 42

num_processes: 10

hyperparameters:

exploration_constant:

type: values

values: [0.2, 0.35, 0.5, 1.0, 1.41, 2.0, 3.0]

fpu_reduction:

type: values

values: [null, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5]

max_simulation_depth:

type: fixed

value: null

widening_constant:

type: values

values: [null, 8.0, 12.0, 16.0, 20.0]

rave_constant:

type: fixed

value: null

output:

directory: null

filename: tuning_results.json

display:

top_n: 10

verbose: trueEach configuration plays 100 games against a random opponent, alternating which side the MCTS player controls.

This produces an output file, tuning_results.json, containing an array with entries like this:

{

"hyperparameters": {

"exploration_constant": 0.2,

"fpu_reduction": null,

"max_simulation_depth": null,

"widening_constant": null,

"rave_constant": null

},

"win_rate": 0.56,

"games_played": 100,

"wins": 56,

"losses": 44,

"ties": 0,

"mean_time_per_game": 0.5422177587635815,

"timestamp": "2025-10-31 10:59:08"

}It also produces a text file containing a summarization of the results, as shown:

================================================================================

MCTS HYPERPARAMETER TUNING RESULTS

================================================================================

Start time: 2025-10-31 12:46:52

End time: 2025-10-31 12:46:52

Duration: 0s

Total time: 17m 14s (includes previous runs)

================================================================================

TOP 10 CONFIGURATIONS (by win rate)

================================================================================

#1: Win rate: 94.0% (94W/6L/0T)

Exploration constant: 0.350

FPU reduction: 0.500

Max depth: Full game

Progressive widening: Yes (constant=12.0)

RAVE: No

Avg time/game: 0.476s

Timestamp: 2025-10-31 11:03:22

--- SNIP ---

#10: Win rate: 89.0% (89W/11L/0T)

Exploration constant: 0.200

FPU reduction: 0.300

Max depth: Full game

Progressive widening: Yes (constant=8.0)

RAVE: No

Avg time/game: 0.421s

Timestamp: 2025-10-31 11:00:34

================================================================================

CODE VERSION

================================================================================

Git version: 8ae9538-dirty

Code hash: 089312841c7381e9Results

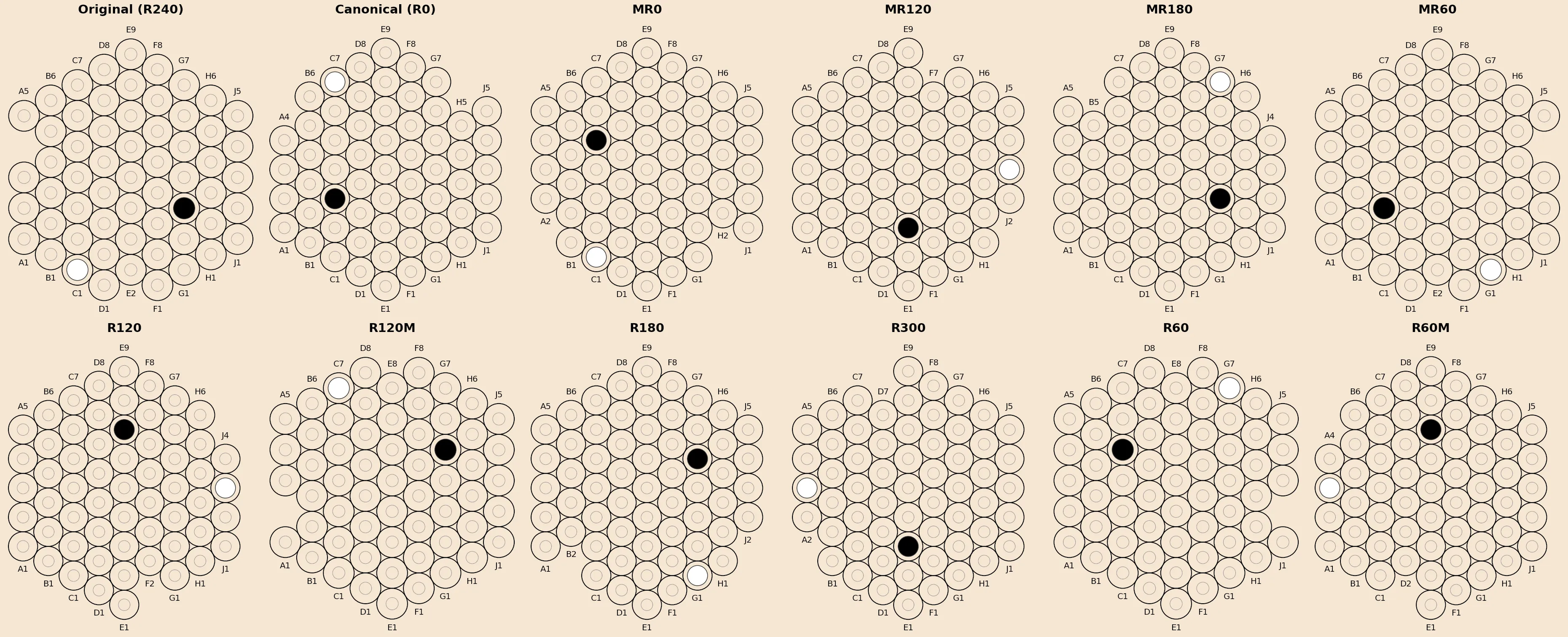

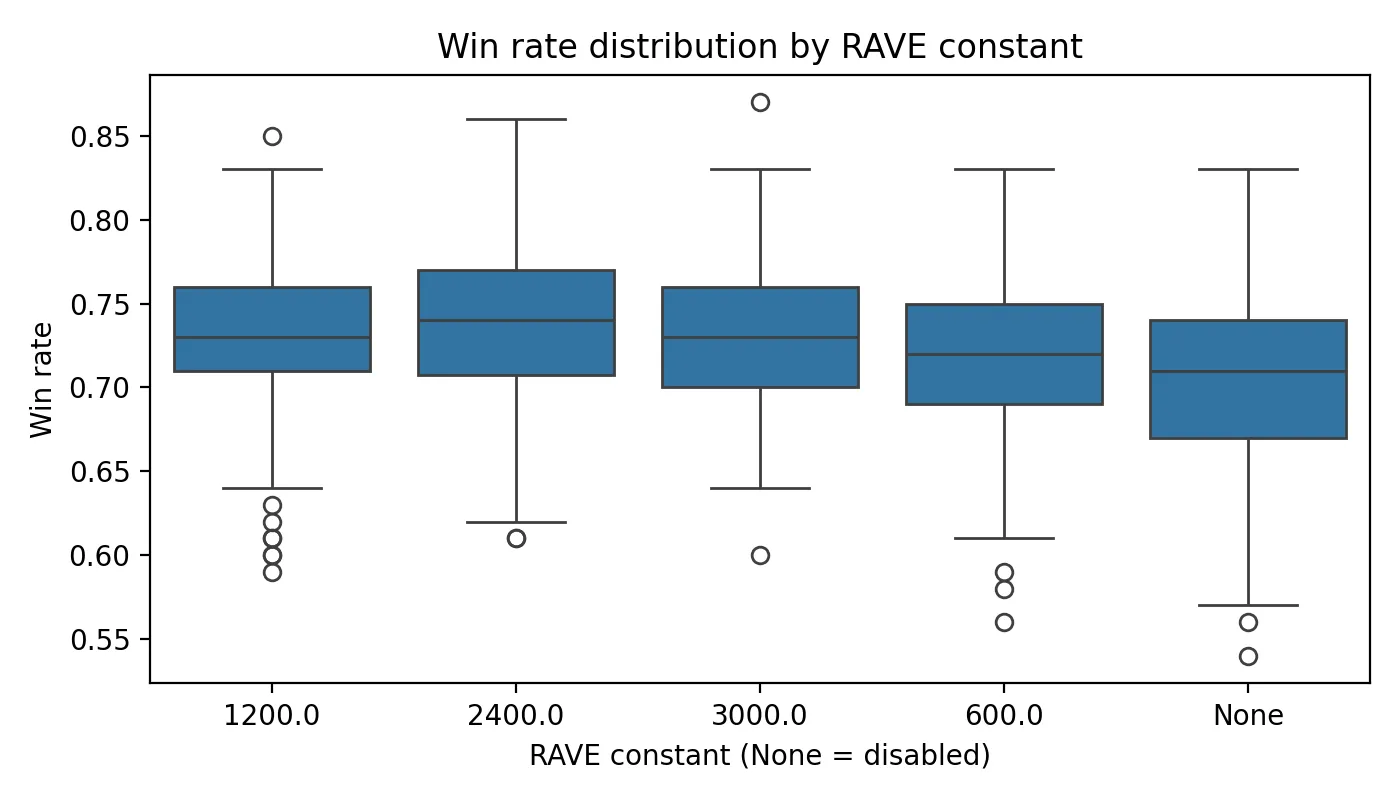

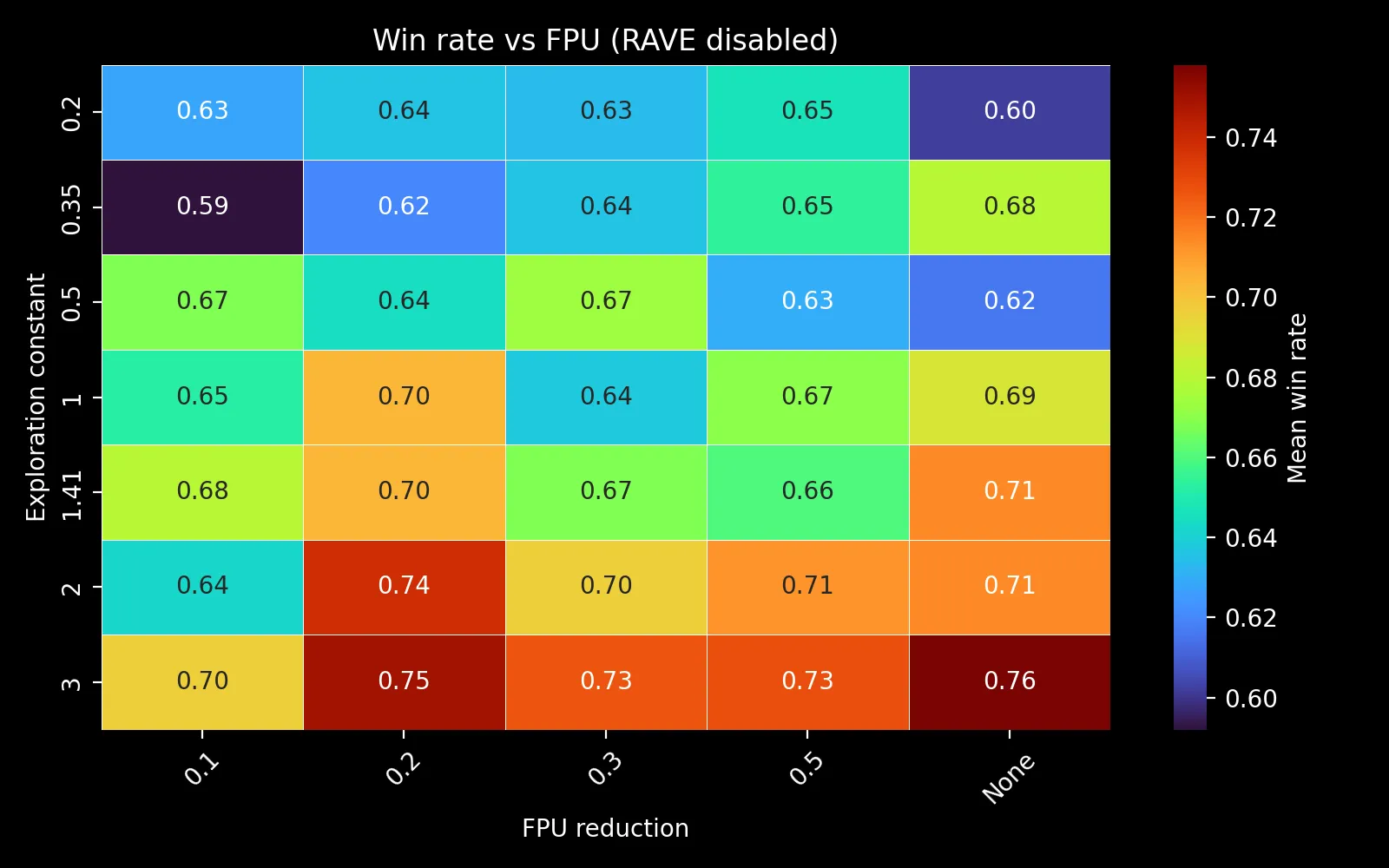

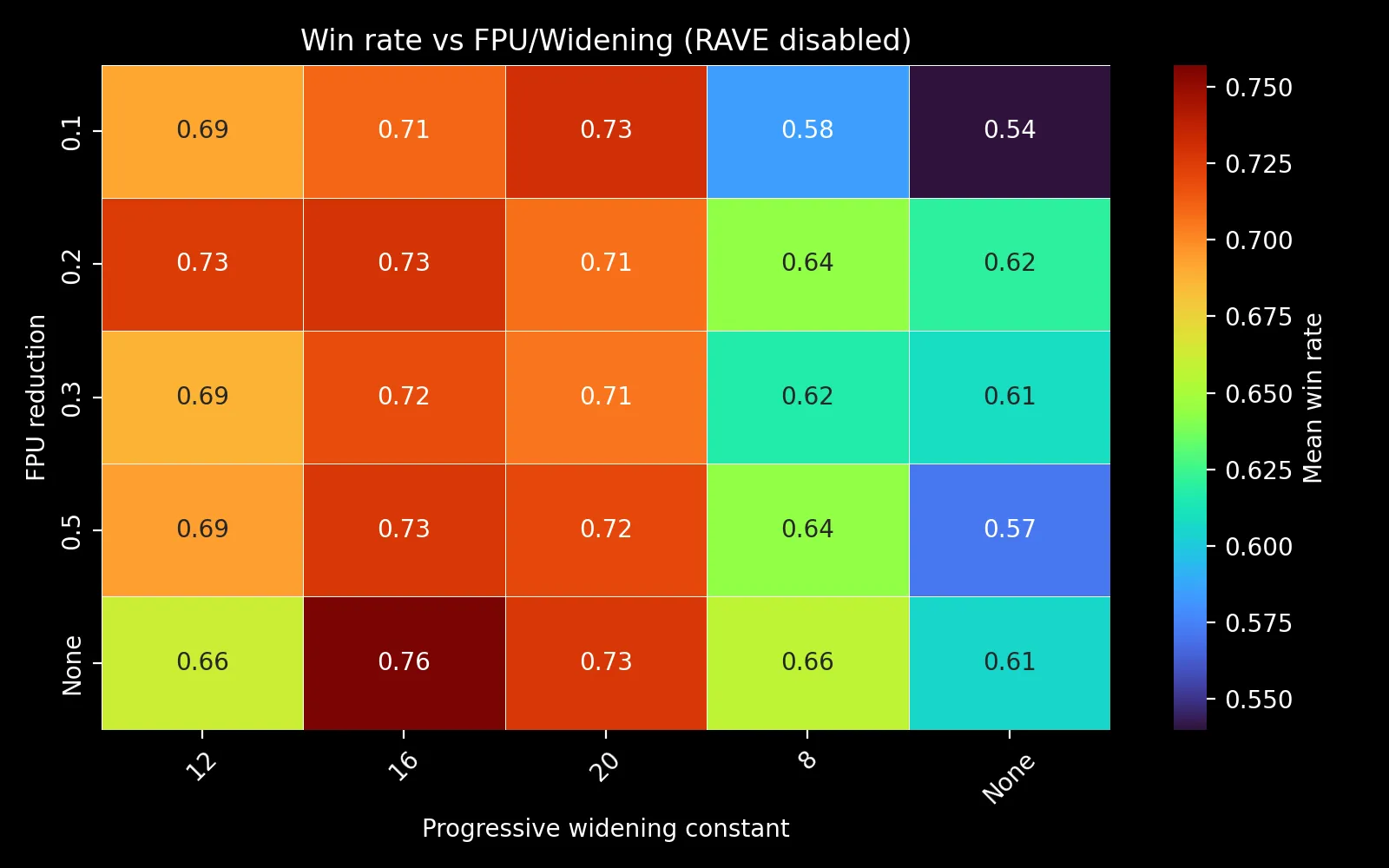

The following plots visualize the tuning results. Note that the scatter plot and heatmaps are from runs with correct chain capture enforcement (post-fix), while the RAVE boxplot is from an earlier comprehensive run. The relative comparison remains valid since all configurations in that run used the same code.

The scatter plot reveals two distinct clusters. The left cluster (4-6 seconds per game, 60-87% win rate) represents configurations with progressive widening enabled. The right cluster (8-9.5 seconds per game, 53-65% win rate) represents configurations without progressive widening — note the absence of green in those points’ RGB encoding.

The difference is definitely noticeable: disabling progressive widening both doubles game time and reduces win rate by 15-20 percentage points. Without widening, the search spreads iterations across all legal moves equally, diluting effort on unpromising branches. With widening, early iterations focus on a subset of moves, deepening analysis of the most promising lines before gradually expanding consideration to alternatives. This focused search achieves better results in less time — a clear Pareto improvement.

RAVE provides no benefit: The boxplot comparison makes this clear.

My hypothesis is that RAVE’s underlying assumption – that a move’s value transfers across contexts – does not hold well in Zèrtz. The mandatory capture rules mean that the value of placing a marble at position X depends heavily on the specific board configuration rather than being a context-independent property of X.

FPU reduction shows no strong trend: The heatmap of exploration constant versus FPU reduction shows win rates bouncing between 70-87% without a clear pattern.

Progressive widening is beneficial but not sensitive: Values of 8, 12, and 16 all perform similarly.

High exploration constants perform well: The tuning grid included exploration constants from 0.2 to 3.0. Higher values (2.0-3.0) consistently outperformed the theoretical optimum of

Validation

To assess variance, I ran the best configuration for 100 repetitions of 100-game matches:

Mean (SD): 87.6% (3.2%)

95% CI: [87.0%, 88.2%]

Median: 87.0%

Range: [80.0%, 95.0%]An 88% win rate against random play is reasonable[3]. Zèrtz is not trivially solvable by search – the mandatory capture rules mean that even random play occasionally stumbles into forcing sequences.

Lessons Learned

Several observations from this phase of development:

- Visualization is worth the investment: The Panda3D renderer and board diagram tools caught bugs that unit tests missed. Being able to watch the AI play and visually inspect board states accelerated debugging significantly.

- Canonicalization justifies its complexity: The 60-80% transposition table hit rates speak for themselves. For any game with symmetry, state canonicalization should be considered essential infrastructure.

- Prototype in Python, port the hot path: The Python MCTS implementation allowed rapid iteration on the algorithm. Once the logic was correct, the Rust port was tedious but straightforward. Attempting to write correct Rust from the start would have been slower.

- Parity tests are essential when rewriting: The 400+ lines of Python-versus-Rust comparison tests caught bugs that would have taken substantial time to diagnose otherwise.

- Benchmark before deleting: I have no clean Python versus Rust timing comparisons because I removed the Python code before being disciplined about measurement. I could go ahead and faff around with git history, but it would be a pain and probably not worth the effort. Anecdotally though, the Rust implementation is much much faster, by several orders of magnitude.

- Parallelism isn’t always faster: Parallel MCTS with virtual loss sounds like an obvious win. In practice, lock contention at tree nodes made it slower than serial search for typical iteration counts. The lesson: measure before assuming concurrency helps.

- Implement a simple game first: Tic-Tac-Toe took a day to implement but caught multiple bugs in the generic MCTS code that Zèrtz’s complexity had masked. A minimal reference implementation pays for itself quickly.

Next Steps

The next phase is neural network integration. Zèrtz’s dynamic topology makes GNNs a more natural fit than convolutional architectures (although I did briefly consider implementing a C6 convolutional filter). However, standard convolutions assume a fixed square grid structure, which does not suit Zèrtz, so I decided to proceed with an investigation into the effectiveness of GNNs in this problem domain.

The GNN would provide value estimates and move priors to guide MCTS, following the AlphaZero paradigm. This work is in progress and will be the subject of a future post.

The code is available at github.com/hiive/Zertz3D . The MCTS engine is functional and the tuning infrastructure is solid, though the project remains a work in progress.

Footnotes

1.

I’ve got my eye on Dvonn ![]() as the next target, followed by the rest of the project: Lyngk

as the next target, followed by the rest of the project: Lyngk ![]() , Yinsh

, Yinsh ![]() , Tzaar

, Tzaar ![]() , Gipf

, Gipf ![]() , Matrx Gipf

, Matrx Gipf ![]() and possibly Pünct

and possibly Pünct ![]() , (in roughly that order), depending on how this pilot goes. I’d also like to do Hive

, (in roughly that order), depending on how this pilot goes. I’d also like to do Hive ![]() , Ingenious

, Ingenious ![]() and a whole bunch of other (mostly) hex-based games, but seeing as I’m usually (a) hopelessly overoptimistic and (b) easily distracted, I’ll be lucky if I manage to get even this one done – assuming my intended approach even works out.

and a whole bunch of other (mostly) hex-based games, but seeing as I’m usually (a) hopelessly overoptimistic and (b) easily distracted, I’ll be lucky if I manage to get even this one done – assuming my intended approach even works out.

3.

These statistics were collected before subsequent bug fixes to chain capture enforcement. After fixing those bugs, win rate dropped to approximately 70% — not because the AI got worse, but because it now correctly handles edge cases that the random opponent occasionally stumbles into. The “correct” implementation is more principled even if the headline number is lower.

↩